Freud, “Formulations on the Two Principles of Mental Functioning” (1911) (I)

Freud beings “Formulations,” not by directly stating the two principles announced by the title, but by drawing attention to a mark — perhaps the definitive mark — of neurosis:

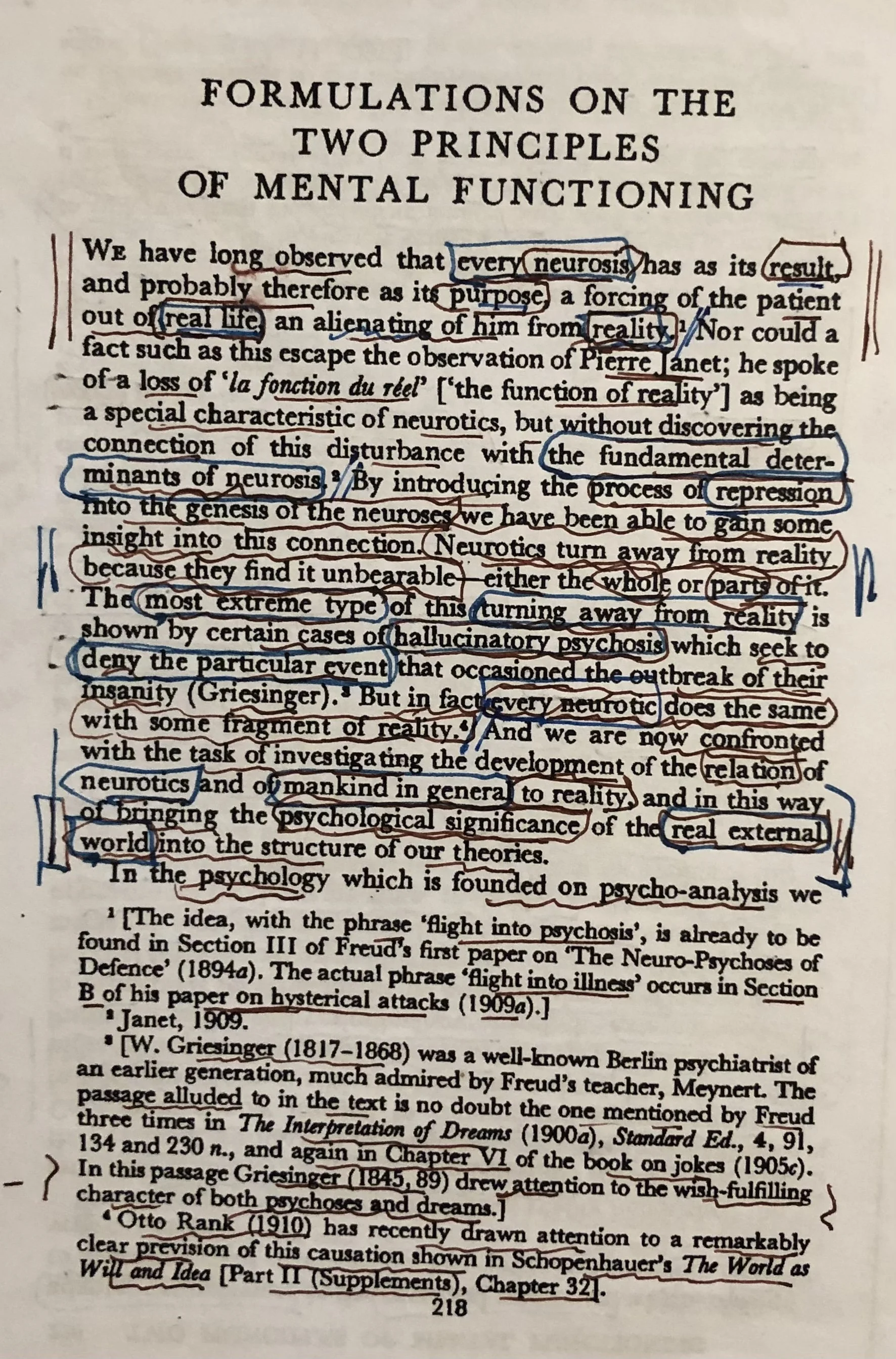

“We have long observed that every neurosis has as its result, and probably therefore as its purpose, a forcing of the patient out of real life, an alienating of him from reality…Neurotics turn away from reality because they find it unbearable — either the whole or parts of it. The most extreme type of this turning away from reality is shown by certain cases of hallucinatory psychosis which seek to deny the particular event that occasioned the outbreak of their insanity. But in fact every neurotic does the same with some fragment of reality.” (218)

We may observe straightaway that Freud does not yet draw the qualitative distinction between neurosis and psychosis that will characterize his later thinking — certainly not in any tidy way. Here, in other words, while mental illness is implicitly plotted along a spectrum from mild to severe, it uniformly involves to some degree an alienation from reality. Later, though, Freud will distinguish sharply, not only between degree of alienation from reality, but between the direction or type of it. In particular, he will suggest that, whereas a neurosis entails an alienation from inner reality (a repression of unacceptable drive derivatives), a psychosis is defined by alienation from outer reality proper (a “denial” of intolerable events in, and features of, the world). (See e.g. the “Fetishism” essay from 1927.)

In any event, and leaving aside any internal differentiation of the “reality alienation” concept, Freud now connects this “disturbance” with “the fundamental determinants of neurosis” (218), that is, its aetiological preconditions. “By introducing the process of repression into the genesis of the neuroses we have been able to gain some insight into this connection” (218).

While Freud’s description here does not yet explicitly enunciate the “pleasure” and “reality” principles per se, it seems to intimate and even demand them. Consider how this first paragraph anticipates the piece’s greater themes: that our relation to reality, to “truth,” is precarious; that when this reality is painful, the neurotic can tolerate only so much of it; that, indeed, when the pain of frankly acknowledging this reality, some truth, surpasses the capacity to endure it, certain defenses are put into operation (denial, repression) that effectively relieve this pain — but at the price of contact with reality, with truth. In other words, there seem to be situations in which one may either maintain “pleasure,” or maintain a hold on “reality” — but not both. And the neurotic is essentially a person who, confronted with such a situation, decides in favor of the former, or sacrifices “reality” to the “pleasure principle.”

The neurotic situation, then, involves an impairment in one’s “reality” sense, “de la function du réel” (218), precisely when and because that reality conflicts with “pleasure.” And those “principles” named in the piece’s title, and their tendency to conflict with one another under conditions of strain — this entire picture is implied in Freud’s introductory conception of neurosis. Hence this conception motivates the remainder of the essay, which is just what Freud now tells us:

“And we are now confronted with the task of investigating the development of the relation of neurotics and of mankind in general to reality, and in this way of bringing the psychological significance of the real external world into the structure of our theories” (218)

Now this description of our “task,” to the execution of which the essay is now dedicated, appears to contain several subtleties.

To begin with, we are considering, not merely the organism’s “relation…to reality” (neurotic or healthy, individual or collective), but rather the “development” of this relation. It goes without saying, for Freud, that the faculty of cognition — broadly, a respect for wish-independent reality and a capacity for truth-apt judgments concerning it — is something remarkable that must be derived from psychological pressures, motivations, and “principles” that antedate this faculty. Such a “relation to reality,” that is, has not always obtained. Nor, having first originated, has it remained in some fixed shaped. On the contrary, it has developed in ways Freud now proposes to reconstruct. (The program is “genealogical,” then, in a way that Nietzsche would recognize.)

Similarly, the second part of the quotation contains a deceptively simple distinction that a reader may easily overlook. The proper object of Freud’s essay is not “the real external world,” but rather “the psychological significance of the external world.” It is ostensibly this “significance” which “the structure of our theories” lack and ought to assimilate. I will not attempt to answer, but only flag some of the questions and ambiguities presented by this distinction, which touches the philosophical core of psychoanalysis. For Freud, science itself — of which psychoanalysis is one perfectly legitimate sector — has exclusively to do with reality. Hence it is, as we will shortly find, the most developed instantiation of the “reality principle.” Its activities and results have achieved the greatest possible autonomy vis-à-vis the pleasure principle. That is, it seeks and honors truth, whether or not the latter happens to “please” or “displease” the seeker. (Later, Freud will qualify this characterization somewhat.)

But if psychoanalysis is itself indeed a science, and therefore has “reality” as its object, we might naively ask: what type of “reality” is Freud examining, both in this piece and in the rest of his corpus? The distinction we emphasized above puts us on the scent. For if we are essentially interested here, not in “external reality” per se, but in its “psychological significance” for an organism in some kind of contact with it, then the term “reality” acquires an equivocal ring. What could “psychological significance” mean in this context? Plainly for Freud it constitutes one piece of reality — otherwise psychoanalysis qua science would not trouble itself with it. Is this “psychic reality,” the object of a clinical analysis, in which what matters is not the patient’s “material” reality — what “really is” the case — but only the “significance” he or she attaches to it?

And so on. I will return to these threads as our commentary proceeds.