Fromm, “The Social Determinants of Psychoanalytic Therapy” (1935) (III)

As we found in our last discussion, in Fromm’s judgment, “Freud…attributed comparatively little importance to the actual behavior and the particular character of the analyst” (151), assuming that the patient’s “transferential" anxiety goes its autonomous way, independently of these qualities. But this prejudice, Fromm continues, is difficult to reconcile with Freud’s own “magnificent achievement” — namely, “to have created this situation of radical openness and truthfulness” (151). More broadly, Freud neglects the humane “ethics” inseparable from his program, preferring the image of the affectless surgeon and describing the analysis itself “as a medical, therapeutic procedure” (151). Yet for Fromm, this medico-technical model not only fails to “capture” the “novel, human side of the situation” (151) — as though it were simply a matter of misdescribing its concrete, lived-reality. Beyond this, the model deforms that lived-reality, making the analytic situation itself less humane, honest, transparent, and the like.

To be sure, Freud introduced innovations that might have counteracted this deformation. He advised the would-be analyst to undergo her own analysis, in order to master unconscious dynamics and remedy “blind spots” that distort her perceptions. And he recommended to her “an objective, unprejudiced, neutral, and benevolent stance towards anything the patient brings forth” (152), for which the norm of “tolerance” became a shorthand. Fromm suggests, however, that in practice these prescriptions began to coincide with the “emotional coldness and indifference” (152) Freud no less frequently idealized.

How exactly the concept of “tolerance” has come to embrace these (seemingly contradictory) semantic elements; what the relation of this concept is to the sociopolitical developments of the era; how this value does not serve, or no longer serves the purposes of psychoanalysis — Fromm addresses these questions in the remainder of his essay (152-164).

The evolving political context of the value of tolerance (152-154) concerns especially “two aspects of tolerance,” which seem to constitute the two endpoints of a spectrum. At one pole, tolerance indicates “mildness of judgment.” According to this use of the concept, we may recognize a position or behavior as unambiguously wrong, while still displaying “tolerance” inasmuch as we are “forbearing” and tend to “excuse the weaknesses of human beings” (152) — to “forgive” persons and actions, the moral inferiority of which we do not doubt. At the opposite pole, tolerance signals, not an attitude of forbearance or forgiveness, but the renunciation of moral judgment entirely: “Judgment itself is viewed as being intolerant and one-sided” (152).

Fromm indicates that the first meaning of tolerance — a mildness of judgment encapsulated by the maxim, “Tout comprendre c’est tout pardonner” — took hold in the early modern era and announced an essentially progressive political orientation:

“Until the 18th century, the call for tolerance had a militant connotation. This call was directed against the state and the church, both of which forbade people to believe in certain things, let alone state them aloud. The fight for tolerance was a fight against the oppression and the silencing of human beings. It was fought by the representatives of the upcoming bourgeoisie who attacked the political and economical chains of the absolutistic state.” (152)

This “call for tolerance” entails no renunciation of moral judgment — indeed, it seems to possess a morality of its own. At stake here is rather the authority of the church and state to impose a (potentially legitimate) morality. This standpoint urges, or even demands, that authorities display “mildness” in their — hitherto rigid and violent — judgment.

By contrast, the second meaning of tolerance — the total renunciation of judgment suggested by another maxim, Frederick the Great’s “Let everyone find salvation according to his own fashion” (152) — should be associated with a distinct political-economic reality:

“The meaning of the concept of tolerance shifted with the victory of the middle classes and their establishment as the ruling class. Formerly the battle cry against oppression and for freedom, tolerance more and more came to stand for an intellectual and moral laissez faire. This kind of tolerance was the prerequisite for a relation between people who met as buyers and sellers in the free market; individuals had to accept themselves as being of equal value, abstractly speaking, regardless of their subjective opinions and standards. They had to view standards of value as something private, which was not to be used for judging an individual. Tolerance became a relativism of values, and the latter were declared as belonging to the private sphere of the individual that was not to be intruded” (152)

I would like to say something about Fromm’s methodological orientation here, since he arranges this history briefly — almost in passing — without alerting the reader to his premises. As I see it, Fromm has in these passages developed a type of ideological analysis sometimes associated with Max Horkheimer — one of whose articles is, indeed, approvingly cited in a footnote. Such an analysis shows how a value or position may serve different ideological “functions,” depending on the surrounding historical constellation. Hence a value such as freedom, justice, or equality will possess distinct meanings — regressive or progressive — that can only be determined in light of these constellations.

(While there are any number of antecedents for this sort of critique, including Marx, one important source is surely the “Second Essay” of Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morality, in which the history of the concept “punishment” is examined at length. Nietzsche shows that this concept contains multiple meanings which depend on the many “purposes” to which the practice has been put, and famously concluding: “[A]ll concepts in which an entire process is semiotically concentrated elude definition; only that which has no history is definable” (GM, II, ¶13). In “Social Determinants,” Fromm’s focus is “tolerance,” and he tacitly follows Nietzsche’s dictum regarding the historicity, hence the overdetermined social function of all values-concepts.)

Thus the value of “tolerance,” which in the early modern period was antagonistic toward the dominant powers — state and church — was gradually co-opted by the ascending class of property-owners as a warrant for its economic interests. Whereas before tolerance checked tyranny, it tended now to eliminate any moral scruple which might interfere with the “free exchange of goods.”

Now, by the time Freud grounds his psychoanalytic ethos in “tolerance,” the value had come to embrace heterogeneous elements as a result of this changing historical function. For Fromm, this heterogeneity or tension would be “reconciled” in a basically mystifying way:

“The concept of liberalistic tolerance, as it was developed in the 19th century, is in itself contradictory: Consciously, there is relativism with regard to any values whatsoever, in the unconscious there is an equally strong condemnation of all violations of taboos" (153)

This full spectrum of meanings was exhibited, Fromm continues, by “the various bourgeois reform movements” (153) — for example, in penal and school reform. Both promoted a naturalistic understanding and explanation of deviant behaviors, the “humane” correction of criminals and the education of children, but on behalf of certain liberal ideals that were never seriously challenged.

“Even the most liberal law reformer would have refused—albeit with all kinds of rationalizations—to have a ”criminal” as a son-in-law, if his daughter wished to marry an embezzler who had spent time in jail” (153)

And similarly with regard to children: “Striving for success, the fulfillment of duty, and respect for facts were the unalterable goals of education” (153). In both cases, taboos with deep psychological roots prevent any application in practice of the “value-free" doctrine preached in word.

Finally, the same sort of tension surfaces in psychoanalysis, and in perhaps its most pointed form:

“The concept of bourgeois-liberal tolerance finds another expression in the psychoanalytic situation. In it, a person is supposed to express, in the presence of another, exactly such thoughts and impulses that are in crassest contradiction to the social taboos; and the other is supposed not to flare up indignantly, not to take a moralistic stance, but to remain unbiased and friendly, in short, to refrain from any judgmental attitude whatsoever…The tolerance of the psychoanalyst…shows the two sides mentioned above: On the one hand he does not judge, remains neutral and objective towards all manifestations; on the other hand, like any other member of his class, he shares the respect for the fundamental social taboos and the dislike for anyone violating them” (153-154)

In terms of the polarity introduced above, Fromm seems to be arguing that, notwithstanding (a) the self-styled “value-free” neutrality of the analytic attitude, according to which the patient’s productions are to be dispassionately observed as would any other “natural” phenomena, (b) a definite moralism continued to cling to that attitude, mainly unconsciously, according to which all the “taboos” of the liberal order — political, economic, sexual — are essentially taken for granted. Indeed: precisely because these taboos and norms are tacitly acknowledged, Freud can help himself to a condescending “mildness of judgment” when speaking, for instance, of the sorry state of neurotics who — owing to their failure to thrive according to dominant legal, economic, and sexual norms — deserve our pity, rather than reproach or punishment.

Fromm, “The Social Determinants of Psychoanalytic Therapy” (1935) (II)

Now, for all Freud’s interest in anxiety, particularly in his later writings, where its importance for repression is described at length, he appeared to remain uninterested in drawing its clinical implications. This indifference is certainly reflected in the “technical” papers, “Recommendations to Physicians Practicing Psycho-Analysis” (1912) and “On Beginning the Treatment” (1913) — to which Fromm critically refers in his own exposition. It may be worthwhile, then, to recall these texts of Freud, in order better to understand and assess Fromm’s account.

In fact, Freud’s pieces are a strong indicator of Fromm’s essential “revisionism” in “Social Determinants,” even in the latter’s opening passages, which are ostensibly confined to reconstructing the “orthodox” position. Fromm writes, for instance:

“What does the intensity of the resistance depend on? According to Freud, and slightly simplified, the answer is as follows: The intensity of resistance is proportionate to the intensity of repression, and the intensity of repression in turn depends on the intensity of anxiety which itself was the cause of repression.” (150)

Yet is this really Freud’s considered position? It seems questionable. Indeed, while the “technical" papers — locus classicus of orthodox analytic technique — contain much about “repression” and “resistance,” they contain nothing at all about “anxiety” — a word that does not appear even once in its pages. In “Beginning the Treatment,” for instance, having explicated the concept of resistance and its centrality to analysis, Freud enumerates the “motive forces” that contribute to overcoming it. Among these Freud includes especially the patient’s neurotic suffering: “The primary motive force in the therapy is the patient’s suffering and the wish to be cured that arises from it” (143).

Freud implies that, once this suffering reaches a certain threshold, it may effectively surpass the distress emanating from resistance. At this point, the neurosis pain has become so unbearable that it renders the resistance pain — the pain of confronting inadmissible material — comparatively welcome. Yet according to Freud’s account here, the patient is unconsciously loathe to approach this material, not because it is anixiety-ridden, but because of the secondary gain generated by the neurosis.

Conspicuously absent from Freud’s pieces, then, is any emphasis on, or even allusion to, anxiety — let alone the analyst’s attitude as a potential “anxiety dissolvent.” This is the omission that Fromm attempts to remedy in “Social Determinants”: the “unconditional positive regard” championed later by client-centered therapy is, it seems, the analyst’s single greatest asset in diminishing the patient’s anxiety and, therefore, weakening the resistances that rest upon that anxiety.

In fact, “omission” is perhaps a misnomer here. It is not as though Freud simply “overlooked” — contingently — the potential usefulness of such an attitude in facilitating the objectives of analysis. Rather, Freud’s entire conception of ideal clinical behavior precludes such an attitude. Or, more accurately: Freud held that the “tolerance” he commended to analysts, and which he himself embodied, suffice for a “friendly, unbiased, and nonjudgmental attitude” (151). In other words, once an analyst has met certain minimal standards — displays the benign disinterest of the surgeon — he can rest assured that any outstanding “anxiety” the patient feels towards him is function of transference. The analyst’s tolerance, easy enough to achieve, makes the remaining anxiety superfluous, that is, objectively unwarranted. This “surplus” anxiety can only be explained, finally, not as an appropriate response to a threat — say, disapproval — belonging to the analytic environment, but as a belated reaction to some perceived threat in the patient’s infantile past:

“Assuming that the analyst does meet this last criterion, it looks as though the strength of the resistance is determined solely by the situation as it existed in childhood, and hardly by the present real relationship between analyst and patient. This is indeed more or less the position taken by Freud and some of his disciples. If only certain general and rather formal conditions have been fulfilled, they are inclined to regard the real personality of the analyst as rather unimportant, and to ascribe to ”transference” any reaction to the analyst—that is, to see it as a repetition of reactions originally directed at other people.” (151)

But Fromm, following Ferenczi’s example, vigorously disputes this premise. The “real” attitude of the analyst, both conscious and unconscious, is far from the natural “given” that Freud’s comments occasionally seem to indicate. Indeed, the very attitude of tolerant indifference, which Freud patterns after the surgeon’s, ultimately precludes the end at which analysis aims: the weakening of resistances and the release of repressions. Far from obviating the patient’s anxiety, this attitude inflames and justifies it. Tolerance, finally, as Freud appropriates and idealizes the value, is far from innocent of a certain moralism — particularly regarding bourgeois taboos — that the neurotic patient cannot but recognize as hostile to many of the repressed impulses analysis is meant to liberate.

“If the patient, however vaguely and instinctively, feels that the analyst takes the same condemnatory stance towards the violation of social taboos as the other persons he has met in his childhood and later on, then the original resistance will not only be transferred into the present analytic situation, but also be produced afresh. Conversely, the less judgmental an attitude the analyst takes, and the more he takes sides, in an unconditional way not to be shaken, with the happiness and well-being of the patient— the weaker the original resistance will become, and the more quickly will it be possible to advance to the repressed material” (151)

In the next entry, I will examine Fromm’s “historical” explanation of this dilemma.

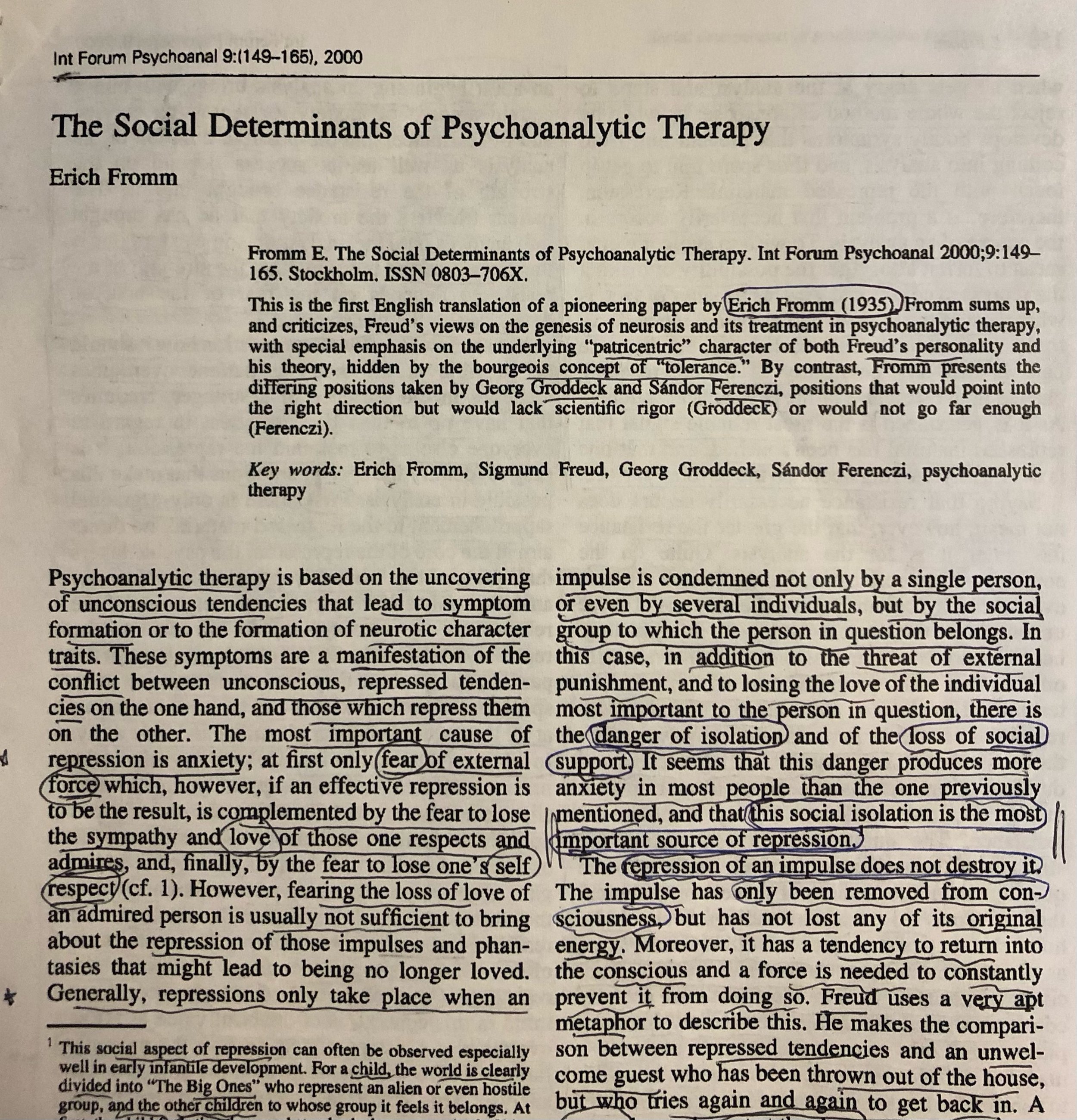

Fromm, “The Social Determinants of Psychoanalytic Therapy” (1935) (I)

Erich Fromm wrote this piece in 1935, while still on relatively friendly terms with his Frankfurt School peers and, one imagines, under their influence. In it, Fromm does a number of things: he offers a useful gloss on the concepts and principles of psychoanalysis, as it was then understood; he reconstructs the historical context — economic, political, more broadly social — that implicitly shaped the psychoanalytic self-understanding; and he develops a critique of that self-understanding, and the clinical practice based upon it, both of which are problematically entangled in that historical context. The critique is internal or “immanent” inasmuch as Fromm judges Freud’s position in terms of its own ideals and aims. Ultimately, argues Fromm, Freud’s clinical recommendations — organized around “tolerance” and related “liberal” norms — conflict with Freud’s own objectives, namely, the effort to release repressions and “make the unconscious conscious.” In short, Fromm critiques Freudian “means” in the name of Freudian “ends.”

In this entry and the following ones, I will take the stages of Fromm’s account in turn: his selective summary of the Freudian “position”; his description of the clinical attitude — “tolerance” — suggested by Freud and the classical tradition; his identification of the socio-historical “content” of this tolerance, which establishes the value-horizon for classical analysis and imposes limitations on clinical efficacy; and his critique of classical therapeutic norms for their unreflective collusion with this value-horizon.

The essay’s first section (149-152) is restricted to recapitulating the main ideas of psychoanalysis, theoretical and clinical — though even here Fromm’s emphasis is selective, and he embroiders his exposition with revisions and criticisms of his own. He begins, uncontroversially, with the claim that psychoanalysis “is based on the uncovering of unconscious tendencies that lead to symptom formation or…neurotic character traits” (149), while continuing — in a slightly more tendentious vein — that the “most important cause of repression,” or the expulsion of these “tendencies” from consciousness in the first place, “is anxiety” (149). But he now, in what is surely an innovative gesture, differentiates this repression-occasioning anxiety into several “types” and, moreover, takes the liberty of ranking their relative pathogenic values. Thus we are invited to distinguish, in ascending significance, (a) the “fear of external force” — by which Fromm must mean “castration threats,” real or imagined; (b) the fear of “los[ing] the sympathy and love” of intimates; (c) fear of losing “one’s self-respect”; (d) finally — the substantial innovation of these passages, though Fromm does not frame it this way — fear of losing social esteem or acceptance. So Fromm writes:

“Generally, repressions only take place when an impulse is condemned not only by a single person, or even by several individuals, but by the social group to which the person in question belongs. In this case, in addition to the threat of external punishment, and to losing the love of the individual most important to the person in question, there is the danger of isolation and of the loss of social support. It seems that this danger produces more anxiety in most people than the one previously mentioned, and that this social isolation is the most important source of repression” (149)

Yet whatever the cause, object, or profundity of the anxiety, the mechanism is much the same: some impulse or package of impulses, originally conscious, seem in practice to evoke such anxiety — because of their effect on significant others in one’s environment — that they must be “repressed,” banished from awareness, where they nonetheless persist as “unconscious.” Repressed impulses are by this definition those the expression of which, hence ultimately even the awareness of which, are felt to imperil their bearers. The power of mind that prevents the re-emergence into awareness of these repressed impulses — which, so to speak, secures and continually renews the repression — is called “resistance.” Since an analysis is dedicated to consciously accessing the unconscious, hence lifting the repressions obstructing that access, it has centrally to do with this “resistance" — all the defensive means at the patient’s disposal for thwarting an analysis, for keeping these impulses unconscious.

Drawing blanks in the midst of free association or flight from distressing material; sudden anger towards the analyst and the analysis itself; illnesses or other symptoms that prevent the patient from attending sessions — all of these may be expressions of resistance. The appearance of these resistances is, Fromm emphasizes, neither an unfortunate accident nor a premonition of clinical failure, but rather “the most reliable signal that repressed material has been touched, and that one is not merely moving about on the psychic surface” (150). The whole substance of analysis, then, consists in eliciting these resistances, in order to address and overcome them. (“Transference” is the most important instrument in this program.)

What exactly is required, though, “in working one’s way through the resistance to the repressed material” (150)? Or again, more specifically: which characteristics of an analyst, and of an analytic situation, will best help in dissolving the resistances, so liberating the repressed impulses into consciousness?

The answer to these questions is connected, of course, to the original problem, namely, “which factors the strength of the resistance depends on” (150). As we saw above, anxiety of a particular sort drives impulses from awareness; it is finally this same anxiety which, via resistance, holds the repression in place. The strength of resistance, then — the necessary analytic obstacle — is a measure of the anxiety surrounding the repressed content. It follows that the effort to weaken the patient’s resistances must at the same time address this anxiety.

Freud, “Constructions in Analysis” (1937) (IV)

As Freud now reiterates, the direct, verbal replies of the patient — reflecting as they do the conscious perspective — are never reliable indices of “correct" and “incorrect.” “Yes” and “No” may well, and often do, mean any number of things. Where should the truth-seeking analyst look, then, in order to ground speculation in something less “ambiguous”?

“It appears, therefore, that the direct utterances of the patient after he has been offered a construction afford very little evidence upon the question whether we have been right or wrong. It is of all the greater interest that there are indirect forms of confirmation which are in every respect trustworthy” (263)

But the problem of interpretation, for all the ingenuity of Freud’s argument, is hardly dissolved in this way. We may certainly distinguish better from worse, more from less plausible, as we go about gathering and assembling evidence. Yet this would not, finally, absolve us of the practical art involved — that is to say, precisely the work of interpretation. We may join Freud in believing that our constructions are “validated” by certain indirect “productions” of the patient: slips, dreams, associations, transferential behaviors, and like. (These signal the construction has “landed,” or has been acknowledged and absorbed by the patient’s unconscious.) And this class of validation is surely better than nothing, as an answer to the question of non-tendentious, durable criteria in psychoanalysis. Again, as Freud puts it:

“Only the further course of the analysis enables us to decide whether our constructions are correct or unserviceable. We do not pretend that an individual construction is anything more than a conjecture which awaits examination, confirmation or rejection.” (265)

Nonetheless, an obvious question remains: how do we determine whether any given “production” in the “further course of the analysis” constitutes the sought-after confirmation? Which of course is precisely to demand, once again: by what criteria are these things to be measured?

Let us imagine an example of the testing-procedure Freud adumbrates, which for clarity’s sake we have simplified into discrete stages — even while noting that Freud himself indicates analysis is in practice never so tidy:

A patient shows up late for several consecutive sessions, and the analyst feels emboldened to interpret, “Your behavior unconsciously expresses hostility.”

The patient, let us say, replies with an emphatic “No,” together with a “rationalization” along the lines of, “The traffic has — quite by chance — been atypically congested the last days, which has prevented my prompt arrival.”

The analyst, following Freud’s example, reserves judgment as to whether or not the interpretation is correct — the patient’s “No,” and his way of consciously explaining his behavior, cannot determine the interpretation’s “truth,” one way or the other. This “No” is “ambiguous.”

So the analyst waits for “indirect” confirmation of the interpretation, in the form of the patient’s spontaneous “productions” following the communication.

Let us suppose that the analyst’s restraint is rewarded by a dream recounted by the patient in the following session — a dream expressing fairly undisguised aggression towards the analyst.

The analyst accordingly considers his interpretation vindicated by a “production” that — indirectly — provides “evidence” of the attributed “unconscious hostility,” in as plain a form as we could hope to encounter it.

Now, if we do accept something like this reconstruction as exemplary of Freud’s interpretation testing-procedure, let us then ask ourselves: what really is the epistemic status of this indirect evidence — in this case, the dream that ostensibly corroborates the original interpretation?

A dream, psychoanalysts suppose — as well as slips and other “symptoms,” for that matter — expresses in manifest form the unconscious, latent layers of mind. But why do we believe this? The answer can only be that we believe this about dreams because of Freud’s arguments based on his interpretations of dreams.

And what about the particular dream recounted by the patient? I have not said what it was; I merely said that it expressed “fairly undisguised aggression against the analyst.” But what sort of dream meets such a description? Perhaps the patient dreamt he felt angry at his analyst and, further, attacked the latter with a hammer. If this dream doesn’t constitute “fairly undisguised aggression,” it is difficult to say what would. But are matters ever so simple?

The very “grammar” of primary process, to which dreams submit, precludes anything like unambiguous, “hard and fast” evidence. The patient’s unconscious thoughts have ex hypothesi been disfigured by displacement, condensation, inversion, and the like. Hence the elements of even so “undisguised” a dream as the one I’ve invented might, on Freud’s own terms, conceal their opposites: the “analyst" in the dream might represent the patient himself, the hostility might express affection, and so on. In any event, the determinate meaning of this dream must itself finally answer to the patient’s associations regarding its individual elements — associations which, scrambled by “resistance,” make interpretation, not less, but more complicated.

But this means: everything depends upon the additional, rolling accumulation of “indirect evidence,” the totality of which might well gradually converge on interpretations and reconstructions that accommodate the most data in the most self-consistent form. Nevertheless, I am suggesting that these interpretations and reconstructions will ultimately be founded, not on extra-interpretive “truth makers” — objective evidence providing the unambiguous “Yes” and “No” that patients cannot deliver directly — but on further interpretations and reconstructions. Once we have divested of authority the patient’s first-person reports regarding the contents of their own minds, we seem to have relinquished any hope of recovering a satisfying criterial “replacement.” Certainly we cannot arbitrarily call a halt to the chain of interpretations, with recourse to some putative “fact of the matter.” For it will always be open to the skeptic to counter: how exactly have you come to that “interpretation”? Note bene: not that scientific judgment.

Freud, “Constructions in Analysis” (1937) (III)

Freud now continues his defense of the analytic, “interpretive” method against charges of arbitrariness and unfalsifiability. He clarifies: “[W]e are not at all inclined to neglect the indications that can be inferred from the patient‘s reaction when we have offered him one of our constructions” (262). The analyst, accused of “invariably twisting his [i.e. the patient’s] remarks into a confirmation” (262), must rather pursue an examination that is “not so simple” (262).

In the following passages, Freud suggests that “Yes” and “No” introduce distinct ambiguities, hence raise different difficulties for the analyst. The patient’s “Yes” — “Your reconstruction of my past is correct” — may reflect an authentic validation, but it may just as easily, perhaps more easily, represent resistance. The patient’s unconscious strategy is then something like, 'I will assent to this reconstruction of my past, and so forestall any further inroads into the genuinely repressed, hence more alarming layers of mind.’ So Freud concludes, in a useful embellishment of the “fecundity” thesis, with the following statement:

“The Yes‘ has no value unless it is followed by indirect confirmations, unless the patient, immediately after his ‘Yes’, produces new memories which complete and extend the construction. Only in such an event do we consider that the Yes‘ has dealt completely with the subject under discussion.” (262)

We may quibble here with Freud’s qualifier — that the sought-after confirmation must arrive “immediately after his ‘Yes’,” in the form of additional, related memories. After all, a moment earlier, Freud is perfectly willing to allow cases in which the “reaction is postponed” (261), which would make the “immediacy” desideratum unnecessary and potentially misleading. (On the other hand, it would be difficult to maintain that only a “No,” and never a “Yes,” may induce postponed confirmation.)

This quibble notwithstanding, Freud’s point is well-taken, since in principle it enables us to discriminate a “resistant” affirmation, devised to throw an analyst off the scent, from a genuine one. The recognition of a construction by the patient’s unconscious “announces” itself by generating fresh material in the neighborhood of that construction. By contrast, Freud implies that an affirmation motivated essentially by resistance would not be accompanied by any spontaneous issue of memories that both validate and amplify the construction.

(Can we not imagine a patient who inadvertently fabricates memories that echo and fill out the analyst’s conjectures, from some combination of motives — say, suggestion, an eagerness to please the analyst, or even resistance itself? This is not a possibility that Freud seems to be aware of, still less one he addresses. Nonetheless, in light of scandals surrounding false “recovered memories,” it is an objection that even charitable readers of Freud may want to raise.)

The patient’s “Yes,” then, is questionable for the reasons Freud describes, and the analyst ought not to receive it as a definitive, or even a tentative confirmation of a construction. All the more, then, will these scruples apply to the patient’s “No,” which “is indeed of even less value” (262) for the purposes of verification. Only in “rare cases,” Freud proposes, is a “No” an “expression of a legitimate dissent” (262). This claim seems to imply at least two things:

By the time a conjecture is formulated and communicated by a conscientious analyst, it must contain some prima facie truth which a patient cannot legitimately reject, at least summarily.

Even where the conjecture is wrong, as a rule the patient’s unconscious — the only arbiter, after all, that matters — simply would not express its rejection in this manner, that is, with a simple “No.” (This may be an adjunct of Freud’s contemporaneous thesis that “negation” has no meaning or reality for the unconscious.)

So Freud continues:

“Far more frequently it expresses a resistance which may have been evoked by the subject-matter of the construction that has been put forward but which may just as easily have arisen from some other factor in the complex analytic situation.” (262-3)

In fact, to repeat, even when the conjecture is altogether mistaken, the patient’s “No” is more likely to signal resistance than a legitimate recognition of its falseness. Freud continues that, where the “No” is grounded in something more than resistance — where its validity is not merely fortuitous — it indicates that the conjecture is not altogether mistaken, but simply “incomplete.” Freud’s point here is intriguing:

“Since every such construction is an incomplete one, since it covers only a small fragment of the forgotten events, we are free to suppose that the patient is not in fact disputing what has been said to him but is basing his contradiction upon the part that has not yet been uncovered. As a rule he will not give his assent until he has learnt the whole truth — which often covers a very great deal of ground. So that the only safe interpretation of his ‘No’ is that it points to incompleteness; there can be no doubt that the construction has not told him everything.” (263)

What are we to make of this position? Freud does not provide an example of a patient’s ‘No’ that points, not to a construction’s patent falseness, but to its incompleteness. He might have several things in mind. A construction such as, “You witnessed your parents having sex when you were an infant,” might be deemed “incomplete” inasmuch as the exact circumstances of the “scene” have not yet been enumerated. (A complete reckoning might accordingly run: “At age one and half, while in your parents’ bedroom, you witnessed them in such-and-such a sexual configuration” — as things turn out in Freud’s “Wolf Man” account.) But the construction might also be viewed as incomplete inasmuch as it is un-supplemented by other, equally general constructions. (In this case, the initial conjecture might be “completed” with the lines: “Before witnessing this scene, you felt your provided all gratification to your mother,” and other, similar addenda.)

Perhaps Freud intended both types of incompleteness. In either case, however, we will certainly want to ask: on what basis does Freud distinguish the one, unequivocal ‘No’ (‘Your conjecture is wrong in toto —nothing like the scene you’ve posited ever occurred’), from the other ‘No’ (‘Your conjecture applies only to a part of my history’)? And then, of course: on what basis does Freud routinely decide in favor of the second?

After all, from the patient’s conscious perspective, the ‘No’ plainly means the first, and emphatically not the second. It is perhaps too obvious to emphasize, but a patient who consciously recognized a conjecture as “partially correct” would not say “No” at all, but rather something like, “Yes — but there are other parts that must be filled in.” So Freud must mean that, nonetheless, from the unconscious perspective, a ‘No’ does announce “Yes, but…” Both Freud’s distinction between “Nos” and his conviction that the “Yes, but…” signification is what generally obtains, awaits some separate justification. Finally, only Freud’s experience with “indirect” evidence licenses the distinction and his conviction regarding it.