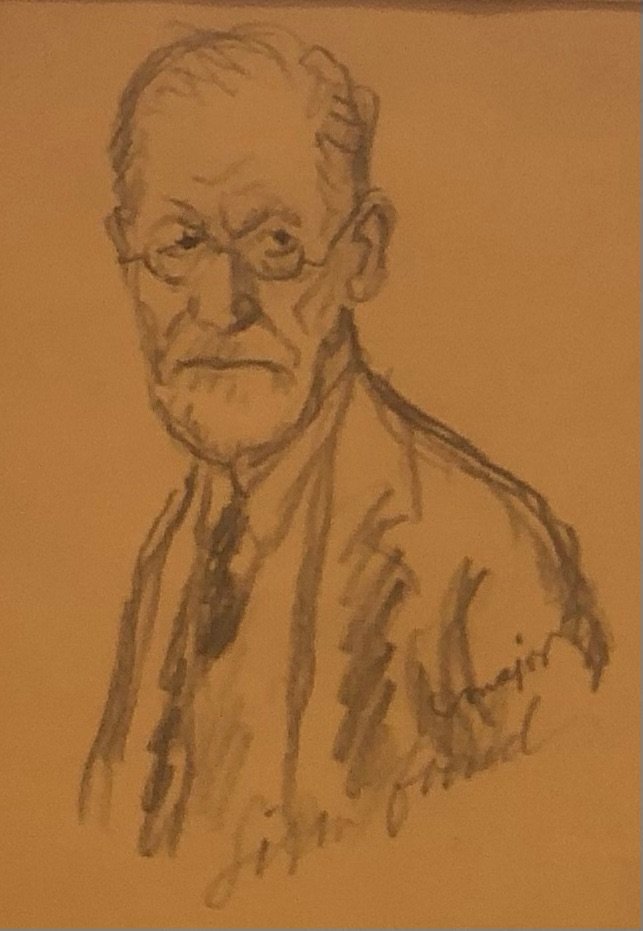

Freud, “The Economic Problem of Masochism” (1924) (IV)

We have seen that, by the time of “Economic Problem,” the “Nirvana” and “pleasure” principles are no longer equivalent. For this reason, the “aims” urged by these principles do not always coincide, though Freud does not exclude the possibility, even the probability, of such a coincidence. In the final analysis, these principles legislate distinct aims, which can and do draw the organism in different directions.

While as a rule, in other words, we can perhaps assume a “coincidence” between the pleasure principle and Nirvana principle, there are situations in which they deviate from one another and come into conflict. In fact, there seem to be a few possibilities which Freud does not take much care to differentiate. Consider the following:

We may imagine a situation in which the pleasure principle and the Nirvana principle, though distinct, are both operative and “determinant” of mental life: one pursues experiences that yield pleasure and, at the same time, reduce tension.

We may likewise imagine situations where abiding by one of these principles appears to exclude — or at least weakens the hegemony of — the other. For instance, one may pursue pleasures that involve a heightening of stimulation. Or — while Freud doesn’t cite any such scenario — one may be compelled towards some tension-reducing behavior or act that is nonetheless felt as unpleasurable.

Finally, we are invited to consider phenomena, among which masochism might be counted, that potentially violate both. On its face, after all, masochism may conform neither to the pleasure principle nor to the constancy principle.

To compound this complexity, let me reiterate what I have suggested in the last couple of entries: it seems that the pleasure principle is irreducibly first-personal. The items “pleasure” and “unpleasure” depend essentially upon our experiencing, that is, our feeling them to be so. To be sure, these feelings must, for Freud, bear some kind of regular connection to the “objective” state of affairs within the organism: the “economic” (as well as the “dynamic” and “topographic”) situation. But beyond this hypothesized “regularity” we cannot say much. To repeat Freud’s words: although “the series of feelings of tension” provide “a direct sense of the increase and decrease of amounts of stimulus” (414), “pleasure” and “unpleasure” themselves “cannot be referred to an increase or decrease of a quantity (which we describe as ‘tension due to stimulus’), although they obviously have a great deal to do with that factor” (414). The pleasure principle, then, is nothing immediately economic, but rather marks the (unknown) manner in which these economics are apprehended.

In any case, let us bracket for now our suspicions and reservations about Freud’s apparent category confusion between first- and third-personal levels. For the most part, I think, Freud himself is scarcely aware of such confusion; for him, the pleasure principle is as fully “objective” as the Nirvana principle.

Principles and Drives

Freud now indicates that, in its “pure" form, the Nirvana principle represents the aim of dissolution or decomposition — drawing backward what is organically “developed” to its less developed, and ultimately inert condition. In other words, the principle is inseparable from Thanatos, the death drive, “whose aim is to conduct the restlessness of life into the stability of the inorganic state” (414).

But in point of fact, neither the Nirvana principle, nor the death drive it expresses, are ever encountered in their “purity.” With the transition from inorganic to organic reality, at any rate, the Nirvana principle’s reign — formerly uncontested — is complicated by its sequel, Eros, as Freud continues:

“[W]e must perceive that the Nirvana principle, belonging as it does to the death instinct, has undergone a modification in living organisms through which it has become the pleasure principle; and we shall henceforward avoid regarding the two principles as one. It is not difficult, if we care to follow up this line of thought, to guess what power was the source of the modification. It can only be the life instinct, the libido, which has thus, alongside of the death instinct, seized upon a share in the regulation of the processes of life. In this way we obtain a small but interesting set of connections. The Nirvana principle expresses the trend of the death instinct; the pleasure principle represents the demands of the libido; and the modification of the latter principle, the reality principle, represents the influence of the external world” (414-415)

In the next entries, I will provide a running commentary to this compact and evocative passage.

Freud, “The Economic Problem of Masochism” (1924) (III)

We have been considering the opening paragraphs of “Economic Problem,” in which Freud suggests that masochism is “mysterious from the economic point of view” (413). In the last entry, we objected that — in fact — Freud underscores masochism’s violation of the (non-economic) “pleasure principle,” rather than the (narrowly economic) “constancy” or “Nirvana” principle. And this is to say: it is not immediately obvious that, and how, masochism represents an “economic” problem at all.

As I suggested, though, Freud can speak in the way he does because, until the time of his article, students of psychoanalysis had imagined the two principles as equivalents. For the reader in 1924, in other words, any violation of the pleasure principle was ipso facto a violation of the constancy principle, hence for that reason an economic problem, after all. As I wrote in the last entry: to seek pain, on this conception, is to excite the very “stimulation” it is the proper task of mind to subdue. In such a situation, masochism really would qualify as a narrowly “economic” problem.

This equivalence was all but codified in “Drives and their Fates” (1915). In this place, Freud defends a “postulate” that we have no trouble recognizing as the “constancy” or "Nirvana” principle:

“[T]he nervous system is an apparatus which has the function of getting rid of the stimuli that reach it, or of reducing them to the lowest possible level; or which, if it were feasible, would maintain itself in an altogether unstimulated condition.” (120)

Freud explicitly relates this “constancy” postulate — one which “assign[s] to the nervous system the task…of mastering stimuli” (120) — to the “pleasure principle” as follows:

“When we further find that the activity of even the most highly developed mental apparatus is subject to the pleasure principle, i.e. is automatically regulated by feelings belonging to the pleasure-unpleasure series, we can hardly reject the further hypothesis that these feelings reflect the manner in which the process of mastering stimuli takes place — certainly in the sense that unpleasurable feelings are connected with an increase and pleasurable feelings with a decrease of stimulus.” (120-121)

Freud’s position in 1915, then, was that feelings of pleasure and unpleasure reflect, in a fairly straightforward way, the “economics” of inner stimuli and their management. In particular, decreases of “excitation” are pleasurable; increases are unpleasurable. Or again: the economic or “objective” task of the mental apparatus, to diminish excitation, is mirrored in the the organism’s “subjective” task of seeking pleasure and avoiding unpleasure. Indeed, it seems to follow that there is really only one principle — seen either under its “third-personal” or “first-personal” aspects.

In fact, as late as Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), Freud appears still to be satisfied with this rough equivalence between the two principles:

“The dominating tendency of mental life, and perhaps of nervous life in general, is the effort to reduce, to keep constant or to remove internal tension due to stimuli (the “Nirvana principle,’ to borrow a term from Barbara Low) —a tendency which finds expression in the pleasure principle…” (55-56)

Now, again, if these are the sorts of formulations that Freud’s readers knew and accepted in 1924, then they’d have had little difficulty supposing that any violation of the pleasure principle was by definition also a violation of the constancy principle — hence “economically” mysterious.

But it is precisely Freud’s purpose at the start of the “Economic Problem” essay to question this equivalence — that is, to distinguish the two principles such that one no longer automatically entails the other. Psychoanalysis has

“attributed to the mental apparatus the purpose of reducing to nothing, or at least of keeping as low as possible, the sums of excitation which flow in upon it…“[W]e have unhesitatingly identified the pleasure-unpleasure principle with this Nirvana principle. Every unpleasure ought thus to coincide with a heightening, and every pleasure with a lowering, of mental tension due to stimulus…But such a view cannot be correct.” (413-414)

What exactly has impelled Freud to question this longstanding assumption of psychoanalysis, namely, the equivalence of the “pleasure” and “constancy” principles? He immediately continues:

“It seems that in the series of feelings of tension we have a direct sense of the increase and decrease of amounts of stimulus, and it cannot be doubted that there are pleasurable tensions and unpleasurable relaxations of tension. The state of sexual excitation is the most striking example of a pleasurable increase of stimulus of this sort, but it is certainly not the only one.” (414)

On the one hand, then, the “series of feelings of tension” do afford us “a direct sense” of the “economics” — “amounts of stimulus” — or the “objective” happenings of the inner world. On the other hand, though, the pleasurable (or unpleasurable) quality of these “feelings” is strictly speaking distinct from the “stimuli” they register, or acquaint us with. Or more precisely: the (decreasing or increasing ) quantities of “stimulus” alone cannot determine the (pleasurable or unpleasurable) quality of these feelings. More or less excitation does not necessarily generate more or less unpleasure, but something else is involved.

What this ‘something else’ is, exactly, is not so simple to say. And while Freud does raise a conjecture here, he ultimately pleads deep uncertainty. Nonetheless, it seems — again — to correspond to something “qualitative” rather than anything “quantitative”:

“Pleasure and unpleasure, therefore, cannot be referred to an increase or decrease of a quantity (which we describe as 'tension due to stimulus'), although they obviously have a great deal to do with that factor. It appears that they depend, not on this quantitative factor, but on some characteristic of it which we can only describe as a qualitative one. If we were able to say what this qualitative characteristic is, we should be much further advanced in psychology. Perhaps it is the rhythm, the temporal sequence of changes, rises and falls in the quantity of stimulus. We do not know.” (414)

Whether, in acknowledging this irreducibly “qualitative” element, Freud has conceded the inadequacy of any “economics” of mind in the strict sense — one confined to examining quantities of stimulus — is I think a question worth asking.

Freud, “The Economic Problem of Masochism” (1924) (II)

I concluded the last entry with some questions raised by the opening paragraph of Freud’s “Economic Problem.” Here again is the paragraph:

“The existence of a masochistic trend in the instinctual life of human beings may justly be described as mysterious from the economic point of view. For if mental processes are governed by the pleasure principle in such a way that their first aim is the avoidance of unpleasure and the obtaining of pleasure, masochism is incomprehensible. If pain and unpleasure can be not simply warnings but actually aims, the pleasure principle is paralysed—it is as though the watchman over our mental life were put out of action by a drug” (413)

Our questions begin with the very first sentence. For what is the nature, exactly, of that perspective — the “economic point of view” — from which the “masochistic trend” shows up as “mysterious?” In the last entry I noted that this text has long been included among Freud’s “metapsychological” works. According to Freud himself, in his 1915 paper “The Unconscious,” the framework of “metapsychology” embraces the following:

“It will not be unreasonable to give a special name to this whole way of regarding our subject-matter, for it is the consummation of psychoanalytic research. I propose that when we have succeeded in describing a psychical process in its [1] dynamic, [2] topographical, and [3] economic aspects, we should speak of it as a metapsychological presentation.” (184, bracketed numbers mine)

The first two “aspects” of a metapsychology are perhaps roughly familiar to most readers. Throughout Freud’s writings, the “dynamic” perspective construes the mind as a site of forces — cooperating or in conflict, as the case may be. The “topographical” perspective, on the other hand, differentiates this same mind into “systems” — so that a given mental item may belong to the layers “unconscious,” “preconscious,” and “conscious.”

In what, however, does the “economic” perspective consist? In the same place, Freud writes:

“We see how we have gradually been led into adopting a third point of view in our account of psychical phenomena. Besides the dynamic and the topographical points of view, we have adopted an economic one. This endeavors to follow out the vicissitudes of amounts of excitation and to arrive at least at some relative estimate of their magnitude.” (184)

An “economic” treatment of mind, then, seems specifically to concern what is quantitative in it: in this place, “amounts of excitation” — their “magnitude” — and thus, we may extrapolate, the drives as quantifiable sources of these inner excitations.

Let us return now to the opening sentence of Freud’s “Economic Problem”: “The existence of a masochistic trend in the instinctual life of human beings may justly be described as mysterious from the economic point of view.” Now if the “masochistic trend” is indeed “mysterious from the economic point of view,” then we may immediately suppose that this trend is not mysterious in relation to the “dynamic" or “topographic” perspectives. Their premises are evidently consistent with masochism both as a “conflictual” entity and one with largely “unconscious” sources. Hence Freud could not have titled his essay either “The Dynamic Problem of Masochism” or “The Topographic Problem of Masochism.

Instead, to repeat, Freud has conceived this neurosis as a narrowly “economic” problem. If masochism is mysterious from the economic perspective, then, we infer this is because it is (seemingly) inconsistent with the psychoanalytic “arithmetical” understanding of excitations in their various magnitudes, or of the mental apparatus in optimally managing these excitations. This, in any case, is our expectation from the forgoing reflections on Freud’s clarifications in “The Unconscious” essay.

And yet this is precisely not what Freud seems to be saying in the opening paragraph as a whole. Instead, there follows a thematic non sequitur. Once again, the next sentences:

“For if mental processes are governed by the pleasure principle in such a way that their first aim is the avoidance of unpleasure and the obtaining of pleasure, masochism is incomprehensible. If pain and unpleasure can be not simply warnings but actually aims, the pleasure principle is paralysed—it is as though the watchman over our mental life were put out of action by a drug” (413)

To be sure, we have little intuitive difficulty grasping the tension between

masochism, the programatic movement toward pain, and

the pleasure principle, which urges us away from pain as its central law

Yet as we just indicated, this hardly constitutes an economic problem sensu stricto. On the contrary, it appears merely to express the perplexity of any folk psychology when confronted with “irrational” human behavior. Here one imagines a commonsense voice: ‘People want to be happy, no? — Why then would they deliberately make themselves unhappy?’

To put this quibble in a slightly different way: the pleasure principle is essentially a first-personal matter. It pertain to the way experience feels, or what it is like, together with the purported “logic” governing it. It has to do, finally, with subjective motivation. Again, however, Freud has led us to expect an account of masochism, not as phenomenologically mysterious — a “mystery” Freud is hardly the first to register — but economically mysterious. For this reason, we may suspect there is some suppressed conceptual link, an omitted premise, to these opening remarks.

And indeed, Freud will presently fill in this missing premise, which involves a theoretical “equivalence” he had until recently taken largely for granted. Briefly stated: masochism is an “economic” problem per se only if, in suspending the pleasure principle, it also suspends the “constancy” or “Nirvana” principle. For the latter principle does pertain to the management of “magnitudes” of excitation, a plainly third-personal, and finally quantitative matter, rather than a first-personal and qualitative one.

We may look a couple paragraphs ahead for Freud’s descriptions of that principle which is recognizably economic, and essentially so. This principle, Freud writes, is an instance of the broader “tendency towards stability” (413) which in the context of mental life is designated the “Nirvana principle” (413). (In other works, again, the same thing appears as the “constancy principle.”) The “economic” perspective, we said above, pertains to quantifiable “amounts of excitation.” Yet in postulating the Nirvana principle, Freud now tells us, psychoanalysis has precisely “attributed to the mental apparatus the purpose of reducing to nothing, or at least of keeping as low as possible, the sums of excitation which flow in upon it” (413). Hence we have no difficulty in perceiving the economic substance of this principle.

Now Freud’s meaning in the first paragraph is somewhat clearer. In that place, recall, Freud emphasized that “mental processes are governed by the pleasure principle” (413). Yet if this pleasure principle is synonymous with the “nirvana principle,” then masochism poses a problem that is not merely phenomenological but economic. In that case, masochism would violate, not only the human being’s uncontroversial desire to avoid pain, but the psychic apparatus’s injunction — third personal and objective — to keep inner stimulation to a bare minimum. To seek pain, on this conception, is to excite the very stimulation it is the proper task of mind to subdue. In such a situation, masochism really would qualify as a narrowly “economic” problem.

I will elaborate on this “equivalence,” and Freud’s reasons for finally rejecting it, in the next entry.

Freud, “The Economic Problem of Masochism” (1924) (I)

My impression is that Freud’s “Economic Problem” is more frequently discussed, or alluded to, than read. On the evidence, it is best known for the questions it raises about Freud’s early conception of drives. I have discussed these questions extensively in previous entries and won’t reproduce all of the details here. Suffice it to recall that Freud’s early drive “model” implicitly undergoes at least three fundamental alterations between the time of “Drives and Their Fates” and the mature thinking inaugurated by Beyond the Pleasure Principle. These alterations are

Taxonomic — Freud no longer speaks of “self-preserving” and “libidinal” drives, but of Eros (which embraces both of the former) and Thanatos

Structural — whatever their labels or types, drives are no longer inner excitations, acting upon the mind, pressing for discharge, but universal functions of unification and dissolution

Functional — relatedly, these drives are no longer bound to the so-called “constancy principle.” The mind’s putative telos of restoring homeostasis when it has been lost, reducing excitation to a minimum — with which the “pleasure principle” had long been equated — is now grasped in a more subtle way

Again, these changes were mainly “implicit,” and — as we quickly find in the present essay — Freud frequently reverts to elements of the first model that have seemingly been surpassed by the second. In the opening pages of “Economic Problem,” Freud is especially concerned to disentangle the nexus of concepts involved in “3.” The “problem” identified in the piece’s title refers, at least initially, to this nexus, which the phenomenon of masochism brings to our attention in an unmistakable way.

In the Penguin Freud Library the essay is included in the volume “On Metapsychology.” This decision was undoubtedly made on the basis of its opening pages. For it is really here — before Freud turns in detail to the essay’s nominal topic, masochism — that certain metapsychological concepts receive renewed attention. The compact excursus describes, differentiates, and connects mature ideas of the drives (still in the process of crystallization) with the “principles” governing human mentality and, to some extent, the biological realm more generally (the nirvana, pleasure, and reality principles). And it does this in terms — further — of (economic) quantities and (phenomenological) qualities, with associated vocabulary (more characteristic of the early model) of “excitations,” “tensions,” “aims,” and so on. In short: if a “metapsychology” has centrally to do with establishing the nature and architecture of mind — the “stuff” out of which it is compounded — together with the motivational “principles” governing its activities, then these pages have as strong a claim to the title as anything Freud wrote. In this entry and the following ones, I will provide a running commentary on this section.

The general connection between empirical observation and theoretical system-building is underscored in the first paragraph. (Of course, it continues to surprise both admirers and detractors of Freud’s conceptual “system” that its innovator explicitly disclaimed any such label. Among Freud’s reasons for ejecting Alfred Adler from the psychoanalytic fold was the latter’s pretension to evolving a “system.”) The occasion for Freud’s argument is a perceived discrepancy between

certain psychoanalytic doxa regarding the mind, its motivations, and hence the underlying “lawfulness” of its behaviors, and

certain clinical data — namely, attitudes, actions, and life-patterns designated “masochistic” — which seem to violate those doxa

More concretely, those neurotic attitudes and behaviors called masochistic appear to challenge the purported hegemony of the “pleasure principle” in mental life.

Now, by the end of these initial remarks, Freud seems to have reconciled this perceived discrepancy — at least to his own satisfaction — such that masochism no longer violates this axiom, but in its own, convoluted way confirms and illustrates it. In order to reach this reconciliation, though, it is first necessary both to clarify the meaning of the pleasure principle (and its relation to several other principles), and, afterwards, to reinterpret masochism itself such that it assorts with the principles thus differentiated. The balance of Freud’s essay is dedicated to this reinterpretation.

(Incidentally, this rhetorical strategy, which involves Freud (a) stating a principle of mind, (b) inviting the reader to share his puzzlement at an observation that evidently violates that principle, before (c) resolving the contradiction — either by reconciling the principle, the observation, or both — is familiar from “Mourning and Melancholia.”)

In the present case, Freud works from both sides at once, encouraging us to re-conceive both masochism and those interrelated principles determining it. Freud begins as follows:

“The existence of a masochistic trend in the instinctual life of human beings may justly be described as mysterious from the economic point of view. For if mental processes are governed by the pleasure principle in such a way that their first aim is the avoidance of unpleasure and the obtaining of pleasure, masochism is incomprehensible. If pain and unpleasure can be not simply warnings but actually aims, the pleasure principle is paralysed—it is as though the watchman over our mental life were put out of action by a drug” (413)

Some of Freud’s meaning in this passage will be cleared up in the following paragraphs. Already, however, a number of questions arise which I think we ought to make explicit, if not answer, straightaway.

What is the “masochistic trend in the instinctual life of human beings?”

What exactly is contained in the “economic point of view”? — how does such a perspective contrast with other ways, psychoanalytic or otherwise, of viewing the matter?

How does the “pleasure principle” relate to, or show up within, the “economic” perspective thus differentiated? — and why should the “masochistic trend” present an economic problem, specifically?

I will continue this commentary in the next entry by taking up these kinds of questions.

Greenberg and Mitchell, Object Relations in Psychoanalytic Theory (1983) (V)

In the last entry I collected in one place some ingredients in the drive-structure model, as a way of reckoning the likelihood of an “accommodation” with the relational-structure model. I suggested that any such accommodation would depend upon which ingredients, specifically, we were hoping to preserve. To reiterate: according to the classical account, drives are

organized by considerations that are narrowly hedonic — pertaining to pleasure and unpleasure. Even in Freud’s mature conception, when (1) the notion of psychic equilibrium, the “constancy principle,” is implicitly revised, and (2) the “death drive” — manifesting psychologically in and as aggression — raises the prospect of some motivation “beyond the pleasure principle,” there is every indication that this distinct motivational stem, though perhaps not itself hedonic, becomes discernible only on account of its complex, uneasy fusion with erotic life, hence (indirectly) yielding its own sort of pleasure.

structurally peculiar: either inner excitations, somatic tensions pressing for discharge, or — later on — trends of unification and dismemberment

classifiable according to distinct typologies: either libidinal and self-preserving, in Freud’s early work, or erotic and death drive infused, in the later.

Now, of the dimensions I’ve isolated here, it seems clear that (b) carries the least likelihood of assimilation by relational thinkers. Whatever meaning tropes like “attachment” and “object-seeking” convey in contemporary discussions, they do not include — seem patently to exclude — tensed, “energic” quantities, continuously inducing the psychic apparatus to “work” — direct and discharge — onto some suitable vehicle; nor would they have much use even for the late Freud’s more amenable tendencies of unification and dissolution, since their abstraction verges on vacuity. Certainly organic life universally evinces both tendencies. But the usefulness of this recognition for analysts — theoretically or clinically — is far from obvious.

Somewhere in the middle, as I’ve been suggesting, is (a). This is, I think, the most intriguing drive “ingredient” of the three. Since the last few entries were dedicated to examining the semantic force of phrases like “pleasure-seeking” and “object-seeking,” I will not elaborate here on the obstacles to their “reconciliation," except to repeat that the aim is worth pursuing.

At the other end of the spectrum, (c) seems to raise the least possible obstacles to the rapprochement in view. After all, nothing will prevent us from introducing another column to the drive-typology. Alongside the “drives” of libido, self-preservation, and aggression, we may clear space for an “object-seeking” drive in our discourse. Whether this novel drive enjoys equal standing vis-à-vis the others, or, indeed, becomes the most important one, in terms of which the others are finally explicable, does not matter so much. A “drive” it remains.

We find several precedents for the theoretical strategy of “derivation” in Freud’s own writings. He, too, feels compelled to address observations of human behavior and mentality that threaten to complicate his account. Such observations incline his theoretical opponents to attribute basic motivational trends to human beings — “drives” — rivaling Freud’s own candidates.

In the “History of the Psychoanalytic Movement,” to take one example, Freud criticizes Alfred Adler for inter alia denying foundational standing to the “libidinal drive.” In other words, Adler fails to recognize certain other observed tendencies — variously called “self-assertion,” the “will to power,” and the “masculine protest” (54-55) — as in the last analysis “epiphenomenal” or derivative of the former.

Likewise, in a section of Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego that bears even more directly on Greenberg and Mitchell’s thesis, Freud insists — with his inimitable self-assurance — that everything going by the names “herd instinct,” sociality, gregariousness, and the like, invested with “foundational” explanatory value by other social and political analysts, is nothing more than a belated “reaction-formation” against Freud’s drives.

Once Freud has recognized his two-fold drives as the only irreducible springs of human motivation (libido and self-preservation; later, Eros and Thanatos), then the full sweep of human experience must be more-or-less disguised expressions of them. Sometimes, these drives are observed in something like their “pure” form — as in “genital” sexual behavior when it is minimally “aim deflected.” Even here, however, Freud would underline the Kantian-flavored caveat that we know and experience, not the drives themselves, but merely their psychical “representative.” We know them, in other words, only inasmuch as they “put the mind to work.”

In most cases, in fact, these drives manifest in ways that are distorted to varying degrees. Consider again the case of a nominal “social instinct,” as it’s assessed in Group Psychology. In that place, Freud construes the “fraternal” feeling of community members for one another, not as an irreducible datum, or an immediate, guileless, “natural” expression of good will, but a highly convoluted and essentially misleading “management” of disavowed aggression. All else, it seems, is similarly reducible. (We might further recall, in this connection, Freud’s “Anal Erotism” piece, which outlines the mechanisms underlying “character” and its development from out of the drives.)

All of this, of course, is broadly of a piece with Freud’s “hermeneutics of suspicion,” his “archaeological reduction” of what is later, more refined, and “higher,” to what is early, primitive, and base. And in this program, nothing incarnates the latter as do libido and aggression. This is continuous, too, with Freud’s position in “Formulations on the Two Principles of Mental Functioning,” namely, that no human activity or achievement entirely transcends the “pleasure principle” — that even science, as close to a sacred telos as one is likely to discover in Freud’s writings, does not embody the “reality principle” alone, but remains irremediably tethered at places to its “pleasure principle” origin (and antipode).

I have allowed myself these comments, which may strike the reader as slightly tangential to the unique “content” of Greenberg and Mitchell’s book — namely, the relational-structure paradigm — precisely for what they suggest about “formal” argumentative strategy. For it may equally be said of thinkers in the relational mould (especially Ronald Fairbairn and Heinz Kohut) that they avail themselves, in a formal way, of this same hermeneutics of suspicion. Only the "direction of fit” is inverted. For now all human phenomena redolent of Freudian drives are “reduced” to something else. They are made distorting ephiphenoma, derivatives — in Kohut’s words, “disintegration products” — of the “irreducible” need for attachment, object-relations, security, and so on.

In any case, and notwithstanding the formidable subtlety and care of their exposition, it seems to me that the authors’ concluding discussion essentially collapses each of these three distinctions into a single, incautious position which only entrenches the “irreconcilable” polarity represented by the two models.