Freud, “Formulations on the Two Principles of Mental Functioning” (1911) (III)

Running Commentary

I concluded the last entry with a remarkable paragraph from “Formulations.” Here, in bold, synoptic strokes, Freud describes and explains the transition in mental functioning — the “momentous step” — from the “pleasure principle” to the “reality principle.” Here again is the paragraph:

“I shall be returning to lines of thought which I have developed elsewhere when I suggest that the state of psychical rest was originally disturbed by the peremptory demands of internal needs. When this happened, whatever was thought of (wished for) was simply presented in a hallucinatory manner, just as still happens to-day with our dream-thoughts every night. It was only the non-occurrence of the expected satisfaction, the disappointment experienced, that led to the abandonment of this attempt at satisfaction by means of hallucination. Instead of it, the psychical apparatus had to decide to form a conception of the real circumstances in the external world and to endeavor to make a real alteration in them. A new principle of mental functioning was thus introduced; what was presented in the mind was no longer what was agreeable but what was real, even if it happened to be disagreeable. This setting-up of the reality principle proved to be a momentous step” (219)

Let us consider each of the sweeping sentences in this paragraph, beginning with the first. For the sake of readability, I have emboldened Freud’s words:

“I shall be returning to lines of thought which I have developed elsewhere when I suggest that the state of psychical rest was originally disturbed by the peremptory demands of internal needs.”

Uncertain that I’d grasped Freud’s meaning correctly in this line and the ones that follow (from James Strachey’s Standard Edition), I consulted both the original German text and the more recent translation by Graham Frankland, published by Penguin in 2001. First, the German:

“Ich greife auf Gedankengänge zurück, die ich an anderer Stelle (im allgemeinen Abschnitt der Traumdeutung) entwickelt habe, wenn ich supponiere, daß der psychische Ruhezustand anfanglich durch die gebieterischen Forderungen der inneren Bedürfnisse gestört wurde.” (231)

And now, Frankland's alternative translation of the same sentence:

“I am relying on trains of thought developed elsewhere (in the general section of the Interpretation of Dreams) when I postulate that the state of equilibrium in the psyche was originally disrupted by the urgent demands of inner needs” (4)

Several differences stand out. Some do not seem to affect our understanding much — for instance, that Freud had interpolated a reference to the Traumdeutung within the sentence itself. (Strachey relegates the reference to a footnote without acknowledging his decision.)

A more interesting difference, which might indeed incline us to another understanding of Freud’s meaning in this sentence, is found in the replacement of Strachey’s “the state of psychic rest” with Frankland’s “the state of equilibrium in the psyche.” The source of this divergence is, in Freud’s German, the phrase “psychische Ruhezustand.”

Now, while Strachey’s “rest” would certainly be an appropriate English term for “Ruhe” (in Ruhezustand) in most contexts, in the present case it seems to verge on the concept of sleep in the strict sense. (This is perhaps encouraged by the proximate reference to the theory of dreams.) Yet Freud plainly has something more general in mind than “rest” in the narrow sense of something cyclically contrasted with “exertion.” After all: what meaning could “rest” have as an original characteristic of prehistoric organic substance, before its transition to that “activity” from which it might need rest? Rest from what, exactly? This is one reason, I think, to prefer Frankland’s “state of equilibrium,” which we might envision — at least logically — antedating some subsequent state of disequilibrium.

But “equilibrium” also has a second, related advantage: it puts us unambiguously in mind of Freud’s “constancy principle,” to which the essay implicitly, continuously alludes. I have discussed this principle at some length in other places, as a rule in connection with Freud’s evolving concept of a drive.

We may recall that, in the later “Economic Problem of Masochism” (1924), Freud is willing for the first time to decouple the (formerly conflated) “constancy” and “pleasure” principles. (He recognizes that, in some cases, an increase of tension may be pleasurable, while a diminishment of tension may be un-pleasurable.) At the time of “Formulations,” however, these principles appear equivalent. Some degree of tension — a product, further, of inner stimuli — is essentially Freud’s “third personal” descriptor for the “first personal” experience of unpleasure, and vice versa.

While not yet articulated in the systematic language of drive theory — only really codified in “Drives and Their Fates” (1915) — such notions, and their implicit assumptions, seem to peer through in a sentence like the one we are now examining. For in Freud’s description of a “psychische Ruhezustand” that is “originally disturbed by the peremptory demands of internal needs,” we are plainly invited to envision a psychic state that is both quiescent, without tension, and also pleasurable (or at least not un-pleasurable). Indeed, only something like “the peremptory demands of internal needs” could credibly introduce such “tension,” wrench the psyche out of its quiescent state, and henceforth, finally, motivate some strategy to restore the lost equilibrium. The quintessential example of such a strategy, as Freud shortly tells us, is the primitive operation of “hallucinatory fulfillment.”

(At this stage of his thinking, Freud does not seem to contemplate the possibility that an original state of equilibrium — absence of tension — might itself be felt as un-pleasurable, might itself demand some activity that heightens this tension. Such a conjecture would presumably point forward to the later concept of Eros, the life-drive, dedicated to establishing ever-larger “unities.”)

In the next entry I will continue my running commentary on our paragraph, beginning with Freud’s implicit picture of a “drive.”

Freud, “Formulations on the Two Principles of Mental Functioning” (1911) (II)

The “unconscious mental processes” are, Freud continues, the accustomed “starting point” of psychoanalytic psychology. He now alludes to, without specifying, the “peculiarities” of these processes. The following lines, however, will recall to students of psychoanalysis the sort of peculiarities in question: “We consider these to be the older, primary processes, the residues of a phase of development in which they were the only kind of mental process” (219). Let us recall that, in Freud’s writings and psychoanalysis more generally, “primary process” designates (as against “secondary process”) a mode or style of thinking characterized by plasticity, mobility, association, contradiction, pun, image, metaphor, and so on. (Though see the clarifying discussion in Charles Brenner’s classic text, An Elementary Textbook of Psychoanalysis, 45-47, where Brenner distinguishes another, albeit related use of the the distinction between primary and secondary process — this one having to do with the (objective, impersonal) “binding” and “unbinding” of libido by the psychic apparatus.)

What these “peculiarities” of primary process thinking all share — apart, perhaps, from their self-evident deficiency when measured against the canons of logically-sound secondary process — is their “purpose.” In particular, as Freud now claims:

“The governing purpose [Tendenz] obeyed by these primary processes is easy to recognize; it is described as the pleasure-unpleasure [Lust-Unlust] principle, or more shortly the pleasure principle. These processes strive towards gaining pleasure; psychical activity draws back from any event which might arouse unpleasure” (219)

To repeat, such pleasure-governed processes are allegedly “residues of a phase of development in which they were the only kind of mental process.” The “phase of development” at issue is rather vaguely defined in this passage, and the remainder of the essay does little to remedy this vagueness. For example: we might imagine, I think with some justification, that Freud is referring to the first epoch of living matter, thus joining his reflections here to the speculative cosmology introduced later in Beyond the Pleasure Principle and developed in Civilization and its Discontents. But we might also imagine, again justifiably, that he is referring to the very first human beings who, essentially similar to and continuous with non-human animals, had yet to evolve any of those traits and capacities that enable reality-responsiveness. Of course, Freud is referring to the state of human beings during infancy, even today, before their “ego capacities,” modes of reality-adaptation, are first activated (Heinz Hartmann). And he is referring, as well, to the persistence of primary process thinking in the adult’s unconscious mental activities. But it seems likely enough that Freud has all of these in mind, simultaneously, and sees no reason to select among them.

We might contemplate the following as an illustration of these ambiguities. In one of the essay’s first footnotes, Freud refers hypothetically — as an objection to his position — to “an organization which was a slave to the pleasure principle and neglected the reality of the external world.” The concept of “an organization” seems so abstract that it is agnostic with regard to the possible interpretations above, or capacious enough to include all of them. When, a moment later, Freud varies his language, and speaks instead of a “psychical system” — something illustrated by the infant-mother dyad, or at least the infant’s inchoate idea of that dyad — we might suppose he has restricted the object of his study to human reality, leaving behind non-human and pre-human reality. But we’d be mistaken, for he then cites the “neat example” [Ein schönes Beispiel] of such a “psychical system” which is “afforded by a bird’s egg with its food supply enclosed in its shell,” since it is “able to satisfy even its nutritional requirements autistically” and “for it, the care provided by its mother is limited to the provision of warmth” (220). Thus once again Freud expands our conception of his object to include the (relatively) rudimentary organization of living matter. (Importantly, Freud cites, not the “analogy” or “symbol” of a bird’s egg, but its “example.”)

There follows now a compact, remarkable paragraph, to the exposition of which the remainder of the essays seems dedicated. This paragraph summarizes Freud’s view of the determinants, the content, and the consequences of a “momentous step” (219), namely, from

a psychic situation in which “pleasure principle” prevails in more or less pure form; to one in which

the mind’s functioning falls increasingly — though never entirely — under the influence of the “reality principle”

Here I will reproduce the paragraph in its entirety, and in the next entries I will comment on each of its parts. Such meticulous attention will repay our efforts, I think, since — again — so much of the easy is grounded in, and illuminated by, the broad claims found in this place. The paragraph runs:

“I shall be returning to lines of thought which I have developed elsewhere when I suggest that the state of psychical rest was originally disturbed by the peremptory demands of internal needs. When this happened, whatever was thought of (wished for) was simply presented in a hallucinatory manner, just as still happens to-day with our dream-thoughts every night. It was only the non-occurrence of the expected satisfaction, the disappointment experienced, that led to the abandonment of this attempt at satisfaction by means of hallucination. Instead of it, the psychical apparatus had to decide to form a conception of the real circumstances in the external world and to endeavor to make a real alteration in them. A new principle of mental functioning was thus introduced; what was presented in the mind was no longer what was agreeable but what was real, even if it happened to be disagreeable. This setting-up of the reality principle proved to be a momentous step” (219)

In the next entry I will begin a running commentary on Freud’s words.

Freud, “Formulations on the Two Principles of Mental Functioning” (1911) (I)

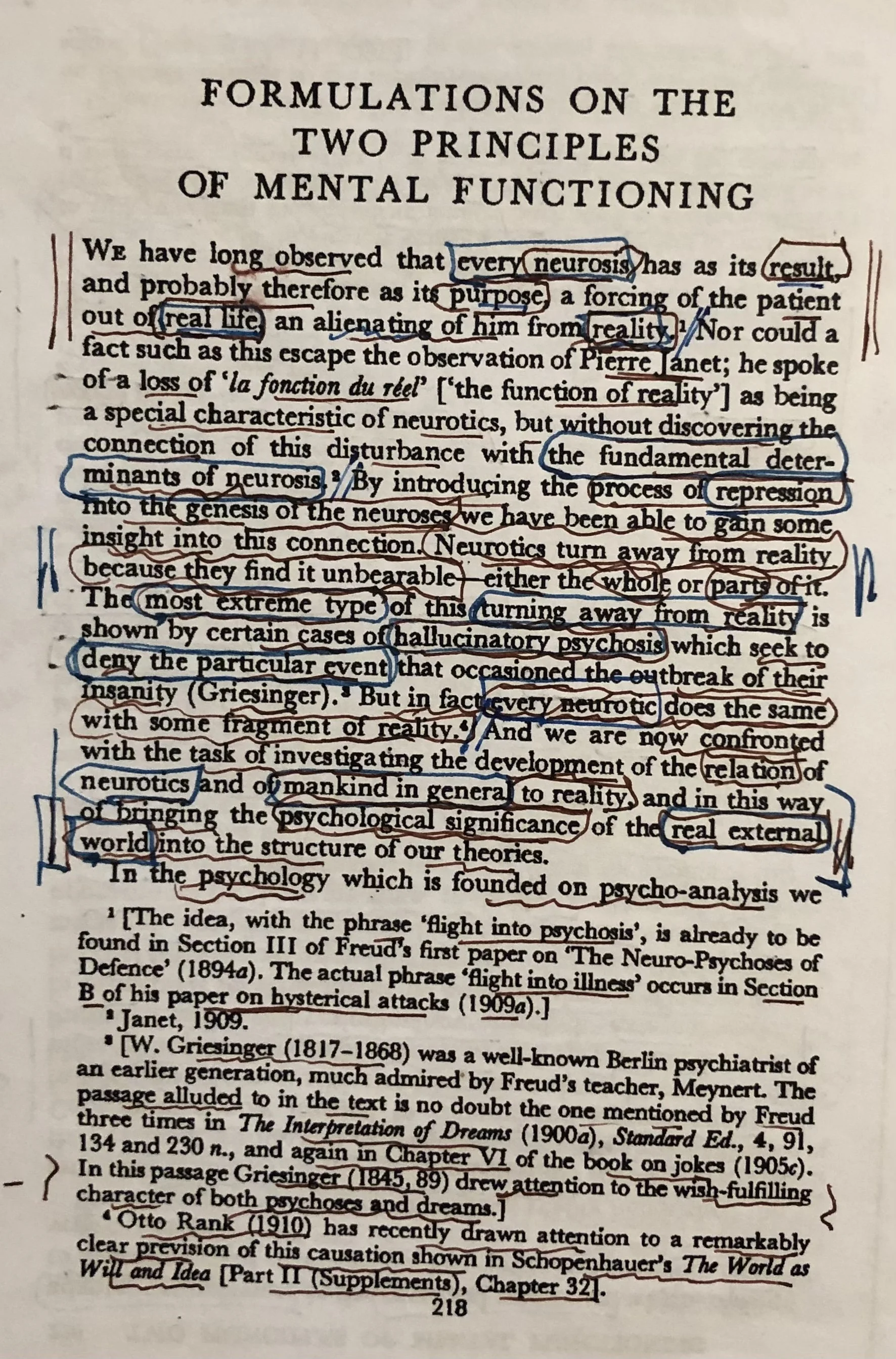

Freud beings “Formulations,” not by directly stating the two principles announced by the title, but by drawing attention to a mark — perhaps the definitive mark — of neurosis:

“We have long observed that every neurosis has as its result, and probably therefore as its purpose, a forcing of the patient out of real life, an alienating of him from reality…Neurotics turn away from reality because they find it unbearable — either the whole or parts of it. The most extreme type of this turning away from reality is shown by certain cases of hallucinatory psychosis which seek to deny the particular event that occasioned the outbreak of their insanity. But in fact every neurotic does the same with some fragment of reality.” (218)

We may observe straightaway that Freud does not yet draw the qualitative distinction between neurosis and psychosis that will characterize his later thinking — certainly not in any tidy way. Here, in other words, while mental illness is implicitly plotted along a spectrum from mild to severe, it uniformly involves to some degree an alienation from reality. Later, though, Freud will distinguish sharply, not only between degree of alienation from reality, but between the direction or type of it. In particular, he will suggest that, whereas a neurosis entails an alienation from inner reality (a repression of unacceptable drive derivatives), a psychosis is defined by alienation from outer reality proper (a “denial” of intolerable events in, and features of, the world). (See e.g. the “Fetishism” essay from 1927.)

In any event, and leaving aside any internal differentiation of the “reality alienation” concept, Freud now connects this “disturbance” with “the fundamental determinants of neurosis” (218), that is, its aetiological preconditions. “By introducing the process of repression into the genesis of the neuroses we have been able to gain some insight into this connection” (218).

While Freud’s description here does not yet explicitly enunciate the “pleasure” and “reality” principles per se, it seems to intimate and even demand them. Consider how this first paragraph anticipates the piece’s greater themes: that our relation to reality, to “truth,” is precarious; that when this reality is painful, the neurotic can tolerate only so much of it; that, indeed, when the pain of frankly acknowledging this reality, some truth, surpasses the capacity to endure it, certain defenses are put into operation (denial, repression) that effectively relieve this pain — but at the price of contact with reality, with truth. In other words, there seem to be situations in which one may either maintain “pleasure,” or maintain a hold on “reality” — but not both. And the neurotic is essentially a person who, confronted with such a situation, decides in favor of the former, or sacrifices “reality” to the “pleasure principle.”

The neurotic situation, then, involves an impairment in one’s “reality” sense, “de la function du réel” (218), precisely when and because that reality conflicts with “pleasure.” And those “principles” named in the piece’s title, and their tendency to conflict with one another under conditions of strain — this entire picture is implied in Freud’s introductory conception of neurosis. Hence this conception motivates the remainder of the essay, which is just what Freud now tells us:

“And we are now confronted with the task of investigating the development of the relation of neurotics and of mankind in general to reality, and in this way of bringing the psychological significance of the real external world into the structure of our theories” (218)

Now this description of our “task,” to the execution of which the essay is now dedicated, appears to contain several subtleties.

To begin with, we are considering, not merely the organism’s “relation…to reality” (neurotic or healthy, individual or collective), but rather the “development” of this relation. It goes without saying, for Freud, that the faculty of cognition — broadly, a respect for wish-independent reality and a capacity for truth-apt judgments concerning it — is something remarkable that must be derived from psychological pressures, motivations, and “principles” that antedate this faculty. Such a “relation to reality,” that is, has not always obtained. Nor, having first originated, has it remained in some fixed shaped. On the contrary, it has developed in ways Freud now proposes to reconstruct. (The program is “genealogical,” then, in a way that Nietzsche would recognize.)

Similarly, the second part of the quotation contains a deceptively simple distinction that a reader may easily overlook. The proper object of Freud’s essay is not “the real external world,” but rather “the psychological significance of the external world.” It is ostensibly this “significance” which “the structure of our theories” lack and ought to assimilate. I will not attempt to answer, but only flag some of the questions and ambiguities presented by this distinction, which touches the philosophical core of psychoanalysis. For Freud, science itself — of which psychoanalysis is one perfectly legitimate sector — has exclusively to do with reality. Hence it is, as we will shortly find, the most developed instantiation of the “reality principle.” Its activities and results have achieved the greatest possible autonomy vis-à-vis the pleasure principle. That is, it seeks and honors truth, whether or not the latter happens to “please” or “displease” the seeker. (Later, Freud will qualify this characterization somewhat.)

But if psychoanalysis is itself indeed a science, and therefore has “reality” as its object, we might naively ask: what type of “reality” is Freud examining, both in this piece and in the rest of his corpus? The distinction we emphasized above puts us on the scent. For if we are essentially interested here, not in “external reality” per se, but in its “psychological significance” for an organism in some kind of contact with it, then the term “reality” acquires an equivocal ring. What could “psychological significance” mean in this context? Plainly for Freud it constitutes one piece of reality — otherwise psychoanalysis qua science would not trouble itself with it. Is this “psychic reality,” the object of a clinical analysis, in which what matters is not the patient’s “material” reality — what “really is” the case — but only the “significance” he or she attaches to it?

And so on. I will return to these threads as our commentary proceeds.

David Black, Psychoanalysis and Ethics: The Necessity of Perspective (2023) (V)

A Coda

In the last entry I concluded a proper “review” of David Black’s Psychoanalysis and Ethics. Here I’d like to revisit a couple lines of thought intimated in the review that, for whatever reason, I wasn’t able to develop.

Psychoanalysis, Science, Philosophy

I suspect that some distinction between “causes” and “ends” — between Aristotle’s “efficient” and “final” causes — would have greatly simplified Black’s account, though perhaps at some cost to its originality. For in a significant way, the question of “positivism’s” historical grip on psychoanalysis — the unambiguous antagonist in Black’s drama — is precisely the question of its uneasy relation to “ends,” to the irreducible place of teleology in human thought and behavior. Drawing this distinction would have brought Black’s ideas into the theoretical ambit established by Paul Ricoeur and Jürgen Habermas, both of whom attempt to reckon with the scientific, efficient-causal ambitions (and pretensions) of psychoanalysis, as compared (especially) to its clinical practice, which presupposes “hermeneutic" and “teleological” forms of of sense-making. A patient’s mental functioning and behavior in a given instance, still less his or her interpersonal integration with the analyst, is never simply caused by antecedent states of affairs, but is always also undertaken “for the sake of” some end. And at a higher level, clinical psychoanalysis itself, even when confined exclusively to interpretation, is unintelligible apart from certain “ends” toward which it is directed: above all, the improved self-awareness, functioning and freedom of the patient.

To be sure, Black himself refers to this distinction, almost in passing, in his review of Jonathan Lear’s work:

“This final cause [shared by diverse psychoanalytic traditions] is the patient’s “freedom”… [T]he recognition of an inherently ethical dimension to psychoanalysis…opens up the possibility that psychoanalysis could in the future found itself on a more coherent and stronger philosophical base than Freud himself, product of the late nineteenth century’s fascination with natural science, was able to give it” (39)

But apart from the single paragraph containing this passage, Black leaves this fundamental idea essentially undeveloped. Again, as I emphasized in the last few entries, the desideratum of a “philosophical base” introduces obscurities that Black never addresses directly. Yet whatever Black means with this metaphor, the project would surely have been advanced by some engagement with, for example, Ricoeur’s Freud and Philosophy, or the many other sophisticated treatments of psychoanalysis’s uneasy relation to science.

Some Notes on “Foundations”

Even the general “foundationalist” program, whatever its ultimate form — broadly, that some “x” must be grounded in some foundation, “y” — ought immediately to raise questions such as:

Does “x” require such a foundation? — do we feel a theoretical or practical “need” for it?

If we do feel such a need, then why? — what are we hoping to accomplish via such a foundation?

Is such a foundation possible?

As I rule, it seems, we must look for answers to such basic questions “between the lines” of Black’s argument.

In fact, this persistent advocacy of a philosophical and ethical “foundation” of psychoanalysis — one allegedly missing from Freud’s original picture but somehow demanded by it — suggests something Black seems to believe without stating openly. The belief is that psychoanalysis is not autonomous in its theory and practice, but is somehow parasitic upon something “extra analytic” it cannot provide from out of its own resources. But what sort of thing is philosophy, and especially those branches of philosophy called “phenomenology” and “ethics,” such that some more “empirical” theory or practice — say, psychoanalysis — stands in need of them?

Sometimes Black’s position seems to be that psychoanalysis has a weak foundation, and our task — with the assistance, perhaps, of Levinas — is to give it a stronger one. All sorts of unfortunate consequences evidently follow from our failure to deliver such a foundation.

At other times, Black suggests that the tradition of psychoanalysis — certainly the work of clinical analysis — is in fairly good shape. Hence we may, as a nearly pro forma gesture or academic exercise, choose to recognize and articulate the philosophical ethics long implicit in this tradition and its practice (particularly in so-called “object relations” psychoanalysis, Black’s favored school). But the analytic tradition itself, the mutual conduct of analyst and analysand, can get along fine without this articulation — it doesn’t require our reflections to do its “work” any more than birds require ornithology to build nests.

Ethics

Ironically, the book does not explicitly address the questions that its title, Psychoanalysis and Ethics, calls most urgently to this reader’s mind, namely: what is or ought to be our “psychoanalytic ethics?” (Or: what is an “ethical psychoanalysis?”)

On the one hand, what sort of ethical conception — values — are implied or demanded by a psychoanalytic understanding of the human condition? (39-40). Or again: what does psychoanalysis have to contribute to the wider ethical discourse? On the other hand, running in the opposite direction: how ought the practice of a clinical psychoanalysis itself to be conducted? — with which values in mind? What end or ends ought a clinician to help realize?

To my mind, many of the most interesting questions belonging to the “psychoanalysis and ethics” nexus arise just here. Ought analysis to have some sort of morally educative role? Does the goal of analysis — hence the job of an effective analyst — include the “improvement” of the patient in some robust moral sense? I imagine most working analysts would disclaim any such “patronizing” presumption. Few would say unreservedly that their “mandate" involves making the patient more virtuous, let alone that a successful analysis brings the patient around to the analyst’s own ethical or political vision. And yet something verging on this presumption may be discerned just beneath the surface of Black’s argument — and sometimes above the surface!

But I have always found that the moral “austerity” of Freud’s vision consists precisely in its non-moralizing substance. This sort of austerity is reflected, for instance, in the famous lines from the Ego and the Id: “[T]he normal man is not only far more immoral than he believes but also far more moral than he knows” (52). For both our immoral impulses (incestuous, murderous) and our moral condemnation of these impulses (in the form of punitive guilt feelings) are largely unconscious. As I suggested in the last entry, however, I occasionally suspect that this “unconscious” layer of mind is precisely what is missing from Black’s account.

David Black, Psychoanalysis and Ethics: The Necessity of Perspective (2023) (IV)

Concluding Comments — A Critique

In a certain sense, however, the steps of Black’s argument seem to run in nearly the opposite direction of the one I’ve recounted, and I want to conclude with a critical observation about this. We saw in the last entry that Descartes begins to mistrust his everyday opinions once he realizes they rest on a weak “foundation.” By contrast, Black, whose central concern is ethics, frequently appears to be arguing something like: ‘Our everyday ethical opinions — our values, intuitions, beliefs, and objects — are unsupported by a “positivist” foundation. Therefore a new foundation is needed, to restore legitimacy to these opinions.’ In other words, whereas Descartes (and Freud, incidentally) begin by throwing doubt on our “everyday opinions,” since they purportedly rest on unsound foundations, Black essentially begins by affirming our “everyday opinions” — broadly speaking, conventional ethical norms and experiences — and insisting that we build a new foundation to support and reinforce those opinions, since the old (and current) foundation does not.

Now, one may certainly appreciate the appeal of such a project. According to Black, the proposed “re-grounding,” if successful, will do human beings a lot of good, promote our individual and collective welfare, and so on. As I indicated at the beginning of this review, the stakes for Black could not be higher:

“[I]n the modern era, neither philosophy nor psychoanalysis has been able to furnish an adequate account of a basis for the compelling power of ethics to motivate decision, or to recognize the values without which humanity is unlikely to survive.” (11)

Or again, in one of the later essays dedicated to Levinas:

“In recent years, the crucial importance of ethical issues has been increasingly recognized both in psychoanalysis and elsewhere. The accelerating dangers in the public domain, to do with climate-change, AI, and mendacious populism have made the devastating consequences of a failure to discover a compelling basis for ethics ever more apparent.” (108)

But the appeal of a theoretical conclusion is no substitute for its feasibility, as surely Black would agree. Freud himself warns us not to mistake a wish for its realization: our need to believe something is no measure of its truth, but on the contrary calls the latter into question all the more insistently.

(For understandable reasons, Black himself takes an ambivalent attitude towards this skepticism, especially as regards Freud’s critique of religion. Black attempts to circumvent the disturbing consequences of this critique by distinguishing between religion-as-belief (that is, in religious objects of various sorts), and religion-as-institutional-support for “epiphantic” ethical experiences that are not themselves matters of “belief” at all. While Black acknowledges the potential “infantilism” of religion under the former description, he defends the legitimacy of the latter.)

Of course, this same Freud, who in Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego notoriously proposed that fraternal love, sociability, and ethical ideals like justice and equality are “reaction formations” against more primitive attitudes of rivalry, envy, and hostility (66), would surely have some critical words for Black, too. But apart from the occasional dismissive comment (e.g. 20, 107-8), Black himself never really engages with the legacy of psychoanalysis in its challenge to our conventional ethical ideas.

(Even Immanuel Kant, that militantly deontological ethical thinker, was forced to concede our helplessness to know, in any given instance, whether our actions really have moral worth, or whether they’ve (perhaps unconsciously) been tainted by sensual inclination and self-love. Hence it is ironic that Black enlists Kant (23) as a philosophical ancestor to Levinasian, “apodictic” ethical experience. Substitute Levinas’s “face of the other” for Romain Rolland’s “oceanic feeling” and one gains a sense both of Black’s objection to the Freudian vision and of Freud’s probable rejoinder to it. In either case, someone propounding a view about the mainspring of ethics or religion appeals to apodictic, first-personal, “phenomenological” experience. Yet the skeptic may always reply: ‘I’ve experienced no such thing.’)

Whatever its merits, the result is surely a domestication of psychoanalysis. Black’s position is evidently that, understood aright, psychoanalytic ideas are none-too-disturbing to our ethical (and religious) assumptions, concerns, and needs. It is rather as though, following Freud’s claim that his “science” — alongside Copernicus and Darwin — has dealt a devastating blow to our narcissistic self-regard, and that our relation to ethical reality is not what it seems, Black emerges to assure us that all is not lost — that, indeed, with a few renovations to our philosophical “foundations,” we will find this relation intact, after all.

Undoubtedly Black would claim — and does (38) — that Freud simply got things wrong here. But his account, as far as I can make out, presupposes, rather than demonstrates, Freud’s error. My own intuition is that precisely the thinker most viscerally repelled by Freud’s critique, as Black appears to be, ought also to be the most wary about this repulsion. One may list all the negative, even catastrophic consequences for human beings following from our failure to “found” or “deduce” our values. Such a situation makes an alternative appealing, indeed, materially and mortally urgent. But it does not in the slightest touch the truth or untruth of that alternative. And a vision that seems to offer the very “consolation” Freud explicitly denied to his teaching should perforce fall under the same suspicions he voiced.